By Cindy Dashnaw Jackson

September 22, 2023

Scholarship awardees want to get medical advances to patients sooner

Ten to 17 years: That’s the most-quoted estimate of how long an advance or discovery in medical research takes to reach physicians and their patients. Reducing this delay is part of what’s driving 2023 Hester Scholarship awardees Sarah Gutch and Emily White. Both are working alongside top immunotherapy researchers who share their goals at the IU Simon Comprehensive Cancer Center.

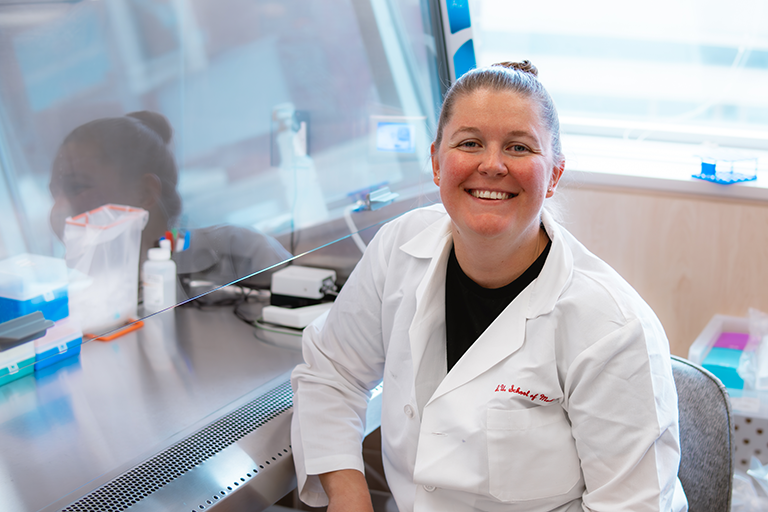

Sarah Gutch

In the IU Simon Comprehensive Cancer Center lab of Maegan Capitano, Ph.D., Sarah Gutch is trying to build on the human body’s ability to repair and keep itself healthy even after the deleterious treatments for blood cancers.

“Patients with a stronger immune system tend to do better and have shorter hospital stays after treatments. Chemotherapy and radiation wipe out the diseased immune system, so we have to give healthy cells back to patients. If we can find ways to improve donated umbilical cord blood, we can improve cell recovery,” Gutch said. “I’ve always found it fascinating that a multitude of complex and powerful processes are occurring simultaneously within something as minuscule as a cell. They are dynamic and complex, especially how cells can interact with one another and produce coordinated responses.”

Gutch intentionally took classes in animal physiology and human anatomy to learn as much as she could about the body in normal and diseased states. For clinical experience, she interned at a biotech start-up that developed drugs for pediatric orphan diseases.

“While I was there, the main drug was at Stage II in clinical trials. Now, it’s FDA-approved and helping millions of children. Knowing I was a part of taking this drug into the clinic is extremely rewarding and a big reason I want to continue in biomedical sciences. Any successful drug begins with research done by trainees like me,” she said.

Gutch then joined Boston Children’s Hospital as a lab technician studying neutrophils, among the earliest white blood cells to attack foreign microorganisms. Deciding to begin a Ph.D. program, she applied to a number of institutions and ended up back in her home state of Indiana and the IU Simon Comprehensive Cancer Center. For now, she’s studying one type of white blood cell called lymphocytes.

“Published data has shown that early lymphocyte recovery is an extremely important step in restoring the immune system. So, if we can improve cord blood transplants in the lab, we could take it to patients. The ultimate goal of improving patients’ lives begins with clinically relevant research,” she said. “Now that I’ve been in the Capitano lab a year, I plan to pursue this specific niche of immunology for years to come.”

The Hester scholarship will take Gutch to the 65th annual American Society of Hematology (ASH) Annual Meeting and Expo and fund high-tech techniques and higher-cost lab supplies.

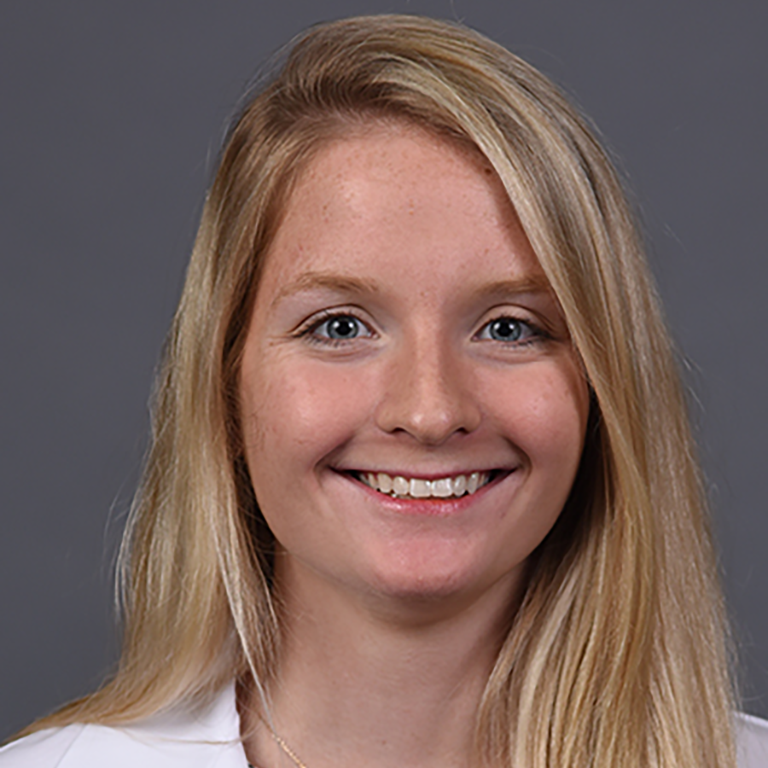

Emily White

‘We are on different wavelengths.’

The unspoken thought brought Emily White up short. In reviewing options for a young cancer patient, White realized that while the attending physician needed to address immediate care, her own questions about common mutations and longer-term issues based on research papers she’d read weren’t addressed.

“The dichotomy showed me the yawning gap between research and therapeutics. There are so many promising discoveries of tumor genetics made in the lab but translating them into medical treatments is a much more difficult task,” she said. “We must bridge this gap to advance cancer therapeutics, and that’s why I’m pursuing a career as an M.D./Ph.D. in biomedical sciences and pediatric oncology research.”

At the IU Simon Comprehensive Cancer Center, White joined Dr. Wade Clapp’s lab with mentor Dr. Steven Rhodes to look for ways to disrupt the potentially deadly progression of tumors in patients with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1). Tumors developing in the nerves of most NF1 patients either stop growing or grow slowly enough to be treated. In others, they become malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNST), the leading cause of early death for NF1 patients.

“Previous data from the Clapp lab has shown that early-stage MPNSTs exhibit a pro-inflammatory, or hot, immune response. Later-stage MPNSTs seem to exhibit a cold immune environment,” she said. “My hypothesis is that understanding this immune transition could contribute to the creation of better diagnostic and therapeutic tools in patients

White proposed this new approach.

“It’s novel in that MPNST progression hasn’t been explored before in the context of immune environments, what the immune system is doing to constrain malignant transformation. I’m lucky they’re letting me explore my idea. If what I’m doing works, it’s an avenue that could go to a clinical trial. That’s ultimately where I want to be, in the translational space of running clinical trials with patients.”

She became a fan of Clapp, Rhodes and the rest of the team even before she joined them in the lab.

“When I was volunteering and doing rotations in peds oncology, what I loved was the clear air of putting the patient first. It’s this collaborative environment between a doctor and patient and parents that’s kind of unique to pediatric oncology,” she said.

White plans to use the Hester scholarship in her NF1 work and to write a National Cancer Institute F30 grant.

About the Author

Cindy Dashnaw Jackson finds and tells nonprofit stories that inspire audiences to share, show up and support. She honed her ability to craft a message that fits an audience during 20 years in nonprofit PR and communications. Now a freelancer and founder of Cause Communications LLC, she's a copywriter and storyteller for nonprofits across the United States. And she earned her degree at IUPUI.