By Cindy Dashnaw Jackson

August 30,2023

Corrected diagnosis saves young father’s life, prompts gift to testicular cancer research

Michael B. Emerick was married, father to an 18-month-old daughter and running four of his own businesses in Florida when severe abdominal pain sent him to a hospital. The harrowing experience that followed proves your cancer doctors’ skill, experience and forthrightness will shape the rest of your life.

In the end, the family of a man who went from a death sentence to a full and cancer-free life would show their gratitude with a major gift to the Indiana University Melvin and Bren Simon Comprehensive Cancer Center.

A nightmare begins

In November 2021, Emerick looked at the CT scans of his abdomen and asked if the largest shape he saw was an organ. No, replied his original physician; it’s a mass of malignant tumors from testicular cancer. But since doctors didn’t seem too worried, neither was Emerick.

“I was fine, mentally. They said I could do four rounds of chemotherapy without being hospitalized, so we rented a place to stay for three months and started chemo a week later,” he said.

Chemo appeared to have resolved two types of tumors by March 2022; however, doctors still saw disease they thought might be different from his original cancer, such as a non-malignant teratoma (a type of germ cell tumor) or a malignant transformation from teratoma. Biopsies would indicate how to proceed, but Emerick believed in what the doctors said was their experience with this type of surgery and the small chance of malignancy.

Three days later, though, Emerick’s questions revealed a more dire story: He’d need major surgery if they found teratoma or malignantly transformed carcinoma, and some on the medical team lacked confidence in their ability to conduct such a surgery without problems.

Jaclyn Byrer, Emerick’s sister, said surgeons offered three potential and distinct scenarios.

“Best-case scenario, the masses are dead tissue from the chemo. Two, there was the possibility they’d be teratoma, which isn’t deadly but does require surgery to resect,” she said. “The last option was terrifying: The masses would be a malignant transformation of teratoma. If the surgeons found this, they said, there’d be no hope for survival. Even though this was the most unlikely option, the vibe was very doom and gloom. Those conversations were brutal.”

On April 12, 2022, Emerick watched the ceiling roll by as nurses wheeled his gurney into the OR for biopsies and potentially major surgery. Not long after surgeons began, Emerick’s father got a high-five from one who’d left the OR to say the first few biopsies had come back as benign teratoma. Dad bought a celebratory coffee and started calling the family.

Then his phone rang. The surgeon wanted to see him immediately.

“They’d spoken too soon. The remaining biopsies returned as teratoma transformed into adenocarcinoma,” Byrer said. “The surgeon told my dad there was nothing anyone could do for Michael. He might have a year to live. It was emotional whiplash.”

The doctor advised the family not to squander what time Emerick had left in seeking a second opinion. Because the cancer was wrapped around two arteries and involved multiple organs and lymph nodes, they said, removing the cancer would require removing his left kidney and portions of his liver and small bowel. They said he’d never survive the operation.

Getting into the right hands

Unwilling to accept this advice, the Emerick family sought answers elsewhere.

“Even if the doctors were right, it felt so wrong for them to tell us not to try anything else, especially when the patient is 34 years young with a second kid on the way,” his sister said. “So, we didn’t listen. I was on the phone that day trying to get information on second opinions and potential clinical trials. We connected with two oncologists through friends of friends—one at UCLA and one at the American Cancer Society—and both said there was only one person worth getting a second opinion from: Larry Einhorn, MD, at the IU Simon Comprehensive Cancer Center. If there was anyone who could help, they said, it was him.”

Based on their recent experience, Emerick and Byrer didn’t expect to hear from Einhorn for weeks. True to his reputation, though, Einhorn reviewed Emerick’s medical records and called him within days.

The conversation was just the beginning of the many pleasant surprises to come.

“Dr. Einhorn said the surgical notes and the pathology report didn’t match, so he’d made some calls and learned that the initial flash-frozen biopsy sample had been labeled incorrectly, which led to an incorrect diagnosis. They’d reviewed the results again and made a new diagnosis but never told us. The cancer hadn’t mutated. It wasn’t adenocarcinoma. It was pure teratoma,” Emerick said. “This was Easter. I had been following my daughter around finding eggs and thinking, This is the last Easter I’m going to see. And then I heard Dr. Einhorn say to me, ‘This is a stay of execution.’ Basically, he told me I was fine. I was going to live a long, normal life.”

The rest is history. More accurately, the rest is pretty routine, according to Clinton Cary, MD, who headed up the IU Simon Comprehensive Cancer Center surgical team that included Michael House, MD.

Their skills and extensive experience with this type of cancer and surgery allowed Emerick to keep his liver, kidney and gallbladder inside his body while they removed more than three pounds of tumor without problems. In a pre-surgery phone call to Byrer and Emerick, Cary had explained that this surgery is something IU Simon Comprehensive Cancer Center surgeons “do quite a bit of. It’s not going to be easy, but we’ve certainly done more difficult surgeries than yours.”

“After the surgery, Dr. Cary said that even if the teratoma had transformed [into malignancy], he felt like his team could have removed it safely and without removing other organs,” Emerick said. “It was a completely different conversation from the one I had just a month earlier, when the surgical team told me there wasn’t anyone in the world who could do this surgery.”

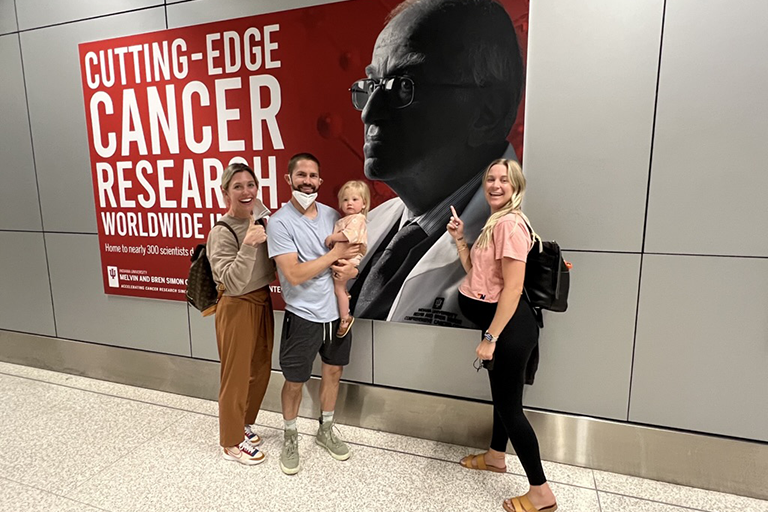

A little more than a month after they’d heard Emerick was terminal, his family was visiting him in his recovery room and sending elated updates to family and friends.

Byrer also sent a note to the man who changed the trajectory of their lives.

“I figured Dr. Einhorn knew the surgery had gone well, but I emailed him anyway and told him I thought Michael would love to see him,” she said. “Dr. Einhorn wrote me back within an hour and visited Michael on a Sunday. It’s no wonder he has a reputation and a legacy. He’s one of the best humans ever.”

On May 24, 2022, Emerick left the hospital a happy man.

Showing gratitude by supporting research

All these events occurred when Emerick and his wife were parenting their 18-month-old daughter and expecting a son, who was born less than three months after Emerick was discharged. So the happy, healthy ending was particularly poignant. In light of the gift he and his family received, Emerick said, their $110,000 gift to the IU Simon Comprehensive Cancer Center’s Testis Cancer Research Fund was an easy decision.

His grandmother Virginia established the Brent and Virginia Emerick Family Foundation before she died at 100, and now family members decide where to send their share of the funds each year.

“With everything that happened, it was a no-brainer for us to give our portion to the IU Simon Comprehensive Cancer Center and specifically for testicular cancer research,” Emerick said.

About the Author

Cindy Dashnaw Jackson finds and tells nonprofit stories that inspire audiences to share, show up and support. She honed her ability to craft a message that fits an audience during 20 years in nonprofit PR and communications. Now a freelancer and founder of Cause Communications LLC, she's a copywriter and storyteller for nonprofits across the United States. And she earned her degree at IUPUI.